A Layman's Approach to Design

How to Engage with Complexity

This essay is adapted from a series of emails that have evolved while on-boarding new clients and from conversations with both clients and colleagues through the course of a project. It could be considered an introduction to "design thinking." My experience has been that almost everyone possesses this trait to a degree, but most of us are not trained to expect uncertainty.

I embarked on a career in design later in life. What I've learned over the course of that transition is that design is essentially a willingness to experiment, fail, learn, and redirect. My intent here is to outline the process of thinking about complexity, and how to approach the feelings that arise from that experience. Much of what is known as popular "design" is really based on a small group of folks with a talent for self-promotion and some skill with the Adobe software suite. Design upon the landscape requires more observational skill and immersive thought than drawing pictures on an iPad. The following is the classical design process taught in landscape architecture programs. My experience is that it is more circuitous and chaotic, following helixes and zig-zags and spirals, rather than straight lines, but linearity is useful when introducing a new idea.

Concepts

Concepts are ideas. I realize this may sound obvious but too often the notion of a "design concept" is obfuscated by an expectation that it needs to be clever. It doesn't. Design is really a method of refining an idea that feels nebulous into a set of definable parameters.

Concepts in the landscape have taken a myriad of forms. The iterations of these forms has given way to a number of typologies, but in all cases these typologies are derived from a set of constraints consistent with the morphology of the surrounding landscape.

If you are considering hiring a professional designer then most likely you already have an idea of what you are looking for. This may be as abstract as knowing you want a patio and a place to cook outdoors, or as specific as a Pinterest board organized with materials and furniture selection. You could be as detailed as selecting the fasteners for the new pergola, or as vague as having a simple desire for shade.

The important thing to note about concepts is that they are inherently flawed. They are illustrations of possibilities that guide the process and inform how the design is tested, but they themselves are untested. Think of them as children, or kittens, or puppies. When you conceive your child or adopt your pet, you have an idea about who or what they will grow into, but seldom do they actually become the person you predict. We change along with the people and ideas that we nurture into being; design concepts are no different. In a way, the concept gives us a direction in which to fail iteratively over the project's lifetime.

Schematics

It is common practice in the conceptual phase to inventory the site and make an analysis of the existing conditions. The central question in this step is where various constraints and opportunities within the site intersect or conflict with your goals. This analysis yields the initial schematics for the final design. I like to introduce some rough numbers during this phase, usually based off municipal code and proximics, to get a sense of how much area to devote to a particular element. The general output from this phase is a rough spatial layout along with an initial cost estimate. In most cases, the concept is still intact.

Development

This is where the design is tested and begins to have a defined geometry. The spatial layout will be edited to fit the topography of the site and details like materials, finishes, furniture, and construction methods will begin to be fleshed out. The design isn't complete, but it is now taking a form where it begins to feel like something achievable.

However...

The Crisis

Every phase of any process has a moment of uncertainty that may escalate into a fiasco. My experience is that this moment occurs primarily during the period where elements of the design are being investigated in detail and tested against various externalities. Often the conceptual and schematic phases generate excitement as the idea progresses from imagination into concrete possibility. But as the drawings develop, specific materials may be unavailable or outside the budget. Sometimes a new code requirement is introduced that prohibits a key feature of the design. Other times a key piece of information is missing from the base data. One of my first projects as a new business owner was a front garden for my brother's new home. He provided me with the plans given to him by his realtor and documentation from the city, but while shopping for an architect he was encouraged to have the property surveyed. The survey revealed that he had a sewer easement cutting across his property, which limited the amount of space he had for improvements. While this information did not interfere with landscape design in the front yard, it did slow down planning for the back and for a proposed addition. These types of mishaps occur all the time in design and construction. Generally, they aren't anyone's fault, but they do create discomfort in the process of implementing a plan.

When not managed correctly, these moments are the source of project abandonment and one-star Google reviews. However, this is where the project can develop a uniqueness and a richness not otherwise found in the course of design execution. While I suspect most businesses either organize around actively avoiding the crisis moment, or at least shielding the customer from it, my approach is to acknowledge and invite that moment as a basis for profound creative discussion. Much as a caterpillar dissolves it's tissue in order to become a butterfly, there is a point in the design process where the set of inspirations that have been borrowed from other projects melt into each other and the final design emerges.

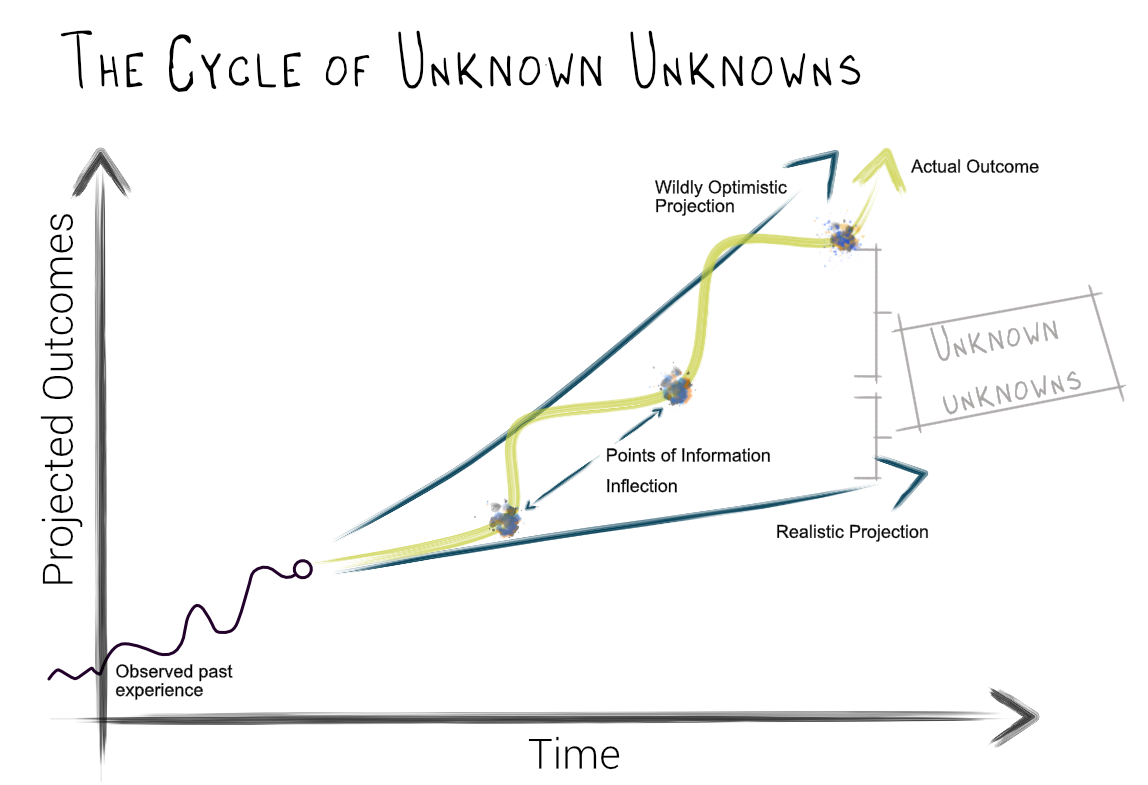

Another way to think about this moment is the method of betting on unknown unknowns. This is a way of anticipating new information and innovations that were concealed during the initial phases of the process. By acknowledging the initial vision as a guiding principle and embracing change along the way, it becomes possible to allow surprises to transform it from utilitarian fantasy into something that exceeds our wildest expectations.

adapted from an image by Alexandr Wang

The "final" design and documentation usually proceeds pretty rapidly after the crisis moment has been resolved. Once done, construction and installation can begin. I will cover this process in another post, but I hope you find this useful as you start to search for people help you with your project, or with beginning your own design.